The Theater in Antiquity - I

The Theater in Antiquity - II

The Theater in the Middle Ages

The Theater in the Early Modern Era

The Theater in the Modern Era

The Theater in the Middle Ages

By Kristin Triff

While the fortunes of the Theater in the early Middle

Ages are unknown, it appears to have retained its architectural

integrity for several centuries. Since the Einsiedeln

Itinerary (a late eighth-century pilgrim’s guide to Rome) refers

specifically to a theatrum near the Church of San Lorenzo

in Damaso, some of Pompey’s buildings may still have been intact at

that time. By the eleventh century, however, the theater had

been partially converted to other uses.

|

|

|

| Santa Maria di Grotta Pinta (deconsecrated, with

seventeenth-century façade) |

These uses include the two churches

that occupy parts of the site, the 11th century

church of Santa Barbara (now Santa Barbara dei Librai, or Saint

Barbara of the booksellers), located near the southern extremity of

the cavea, and the church of Santa Maria di Grottapinta

(“Holy Mary of the painted grotto”) just above the midline of the

cavea. This ancient church, whose earliest surviving

documentation dates from 1186 C.E., was named for the rooms below

the church itself, which were probably the part of an original

access corridor to the cavea. Although the

orientation of the church was reversed in the seventeenth century

and thus the current façade dates to this period, the footprint of

the church remained essentially the same from the Middle Ages

through its deconsecration in the early twentieth century.

|

|

|

| Santa Barbara dei Librai

(seventeenth-century

façade) |

By the mid-twelfth

century, at least two sources still identified the Theater by its

ancient name, while another cities it only as the “Temple of Cneus

(sic) Pompey,” a possible reference to the remains of the Temple of

Venus Victrix which was incorporated into the current Palazzo Pio on

Piazza Biscione. Ten years later (1150 C.E.), the archives of

the Orsini family indicate that “Iohannes de Ceca,” the prior and

financial officer of the church of Sant’Angela in Pescheria (“prior

et yconomus venerabilis Diaconie S. Angeli”), sold part of a

“trullum” to Bobone di Bobone and his heirs. In medieval

Latin, “trullum” derived from the Latin

turris, or tower,

and possibly incorporated the Latin

trulla, or round

structure. Bobone was a direct ancestor of the Orsini family,

one of Rome’s most powerful feudal families, and this sale marks the

beginning of a long association between the Orsini and the remains

of Pompey’s Theater.

|

|

|

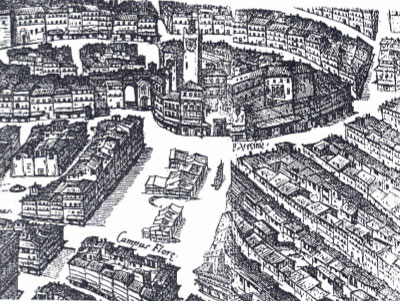

| View of Palazzo Pio looking east from the Campo

de’ Fiori towards the torre dell’ orologio

(Antonio Tempesta, 1606) |

By the end of the thirteenth century, the Boveschi-Orsini had

consolidated their holdings in the southern half of the Theater

through numerous property acquisitions, which included the large

torre dell’orologio, or clocktower built directly atop the

foundation of the Temple of Venus Victrix. The most frequently

cited landmark in the area until its partial destruction in the

seventeenth century, this tower dominated the area around Campo de’

Fiori and was the heart of the Orsini stronghold at this site.

The Orsini palace at Pompey’s Theater was an important link in the

chain of fortified Orsini family properties in the Tiber bend area

of Rome that controlled traffic across the river during the

factional conflicts of the later Middle Ages and

Renaissance.