The Theater in Antiquity - I

The Theater in Antiquity - II

The Theater in the Middle Ages

The Theater in the Early Modern Era

The Theater in the Modern Era

The Theater in Antiquity

By James Packer

|

|

|

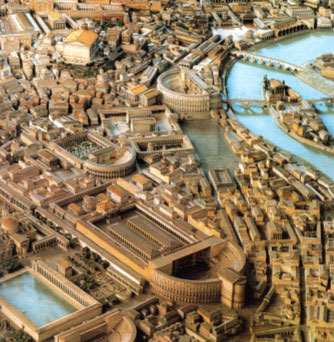

| The Theater of Pompey, restored model

by Italo Gismondi in the Museum of Roman

civilization, Rome |

Dedicated in 55 B.C., the Theater of Pompey the

Great, Rome’s first permanent theater, was an extraordinary

monument. Perfected earlier in local warehouses and amphitheaters,

its impressive new concrete and stone technology – the inspiration

for its original design – allowed Pompey’s architect(s) to locate it

on a flat, marshy plain rather than on a more conventional sloping

hill. Of rectangular blocks of tufa and travertine, its

massive walls were conventional; its concrete vaults, ramping and

horizontal, highly innovational. Combining Hellenistic eastern

models with Italic fashions, its vast size awed its

contemporaries.

|

|

|

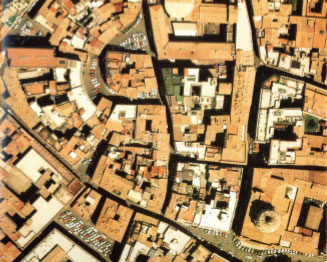

| Aerial view of the Pio Palace from

Piazza del Biscione (semi-circular building, upper

l.,) to Via dei dei Chiavari (long, dark, vertical

street to r.) |

Stretching south from Corso Vittorio Emanuele to Via

Giubbonari and west from Largo Argentina to Campo dei Fiori,

an entire neighborhood occupies the site today. A velarium,

like that of the later Amphitheatrum Flavianum (the Colosseum)

shaded the cavea (the auditorium), and, in addition to the

axially situated Temple of Venus Victrix that crowned the top

of the semi-circular seating area (the cavea), three

smaller shrines to Honor and Virtue, Luck, and Victory stood in the

theater precincts.

|

|

|

|

Interior of the portico behind the Theater of Pompey,

looking NW toward the rear facade of the scaenae frons (G.

Gatteschi, Restauri di Roma imperiale (Rome: Comitato

di Azione Patriotica, 1924, p.

87) |

Behind the scaenae frons (the stage building), a

peristyle with brocaded awnings enclosed lavishly laid out gardens

with avenues of plane trees and a fountain with mythological

statues. At its end, facing the Temple of Venus Victrix, behind the

peristyle colonnade, the Curia Pompeia (guarded by a statue of

Pompey himself) provided the Senate with an elegant new meeting

hall. Pompey’s structures thus served a variety of purposes. The

theater hosted exhibitions, concerts and other musical

presentations, plays, mimes, and quasi-sacred state ceremonies. The

colonnades of the peristyle offered shelter in case of rain and

served as a gallery for paintings and sculpture. The garden was also

a city park, a meeting place for public and private

functions; the curia was a government center.

Significantly, the Theater lay on the southern Campus Martius

beyond Rome’s pomerium (the sacred boundary around

the city). Setting aside the ancient republican strictures against a

permanent theater, Pompey constructed there a prototypical imperial

monument. By its unprecedented design, size, and expensive fittings,

it initially celebrated his fame. Ultimately, after his defeat and

murder, it commemorated his vast personal, political, and military

power. After Caesar’s assassination, the people burned the

Curia Pompeia where he had been murdered. Augustus definitively

closed what was left and moved Pompey’s statue across the gardens to

a spot just behind the main door of the scaenae frons. Thereafter,

until the fall of the Roman Empire, Augustus and his successors

scrupulously maintained the Theater and its dependencies. Only after

the end of the Ostrogothic Kingdom (when, between 507 and 511,

Cassiodorus again repaired the Theater), was it abandoned to slow

decay.