- Home

- History of the Theater

- Excavations & Early Studies

- Site Documentation

- New Excavation

- Archaeological Register

- Publications

- 3D Visualisations

- Italian Theaters

- News

|

[n]

Local Navigation

|

|

|

|

|

|

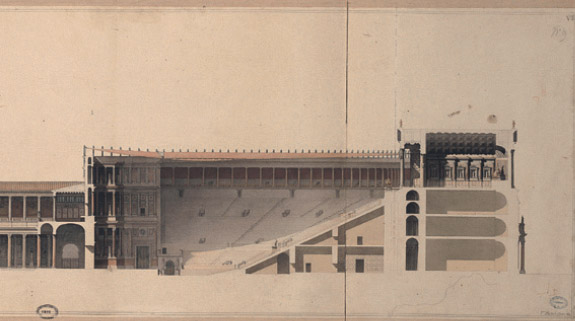

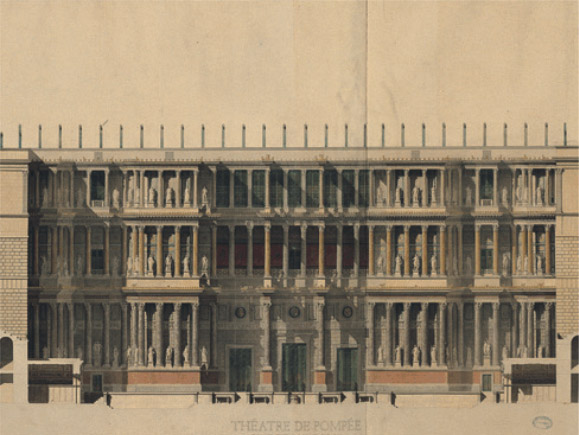

Victoire Baltard, a French Architect on a grant at the French

Academy in Rome, partially confirmed and revised that

reconstruction, and, as required by his grant, made a new

reconstruction of the theater in 1837.

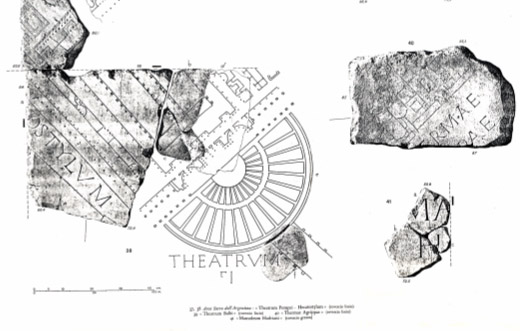

Basing his work on Vitruvius, on fragments of the Forma Urbis,

the early third century C.E. marble plan of Rome, and on the earlier

study of Canina, Baltard also undertook two excavations in the Largo

dei Librari and the Piazza dei Satiri that clarified the extent and

architectural character of the Theater. The first cleared part

of the facade; the second uncovered the east apse of the scaenae

frons and confirmed its plan on the Forma Urbis. First published in

the early 20th century, his drawings have served as the model for

all subsequent reconstructions of the Theater.

The

Theater of Pompey on the Forma Urbis

|

| |

|

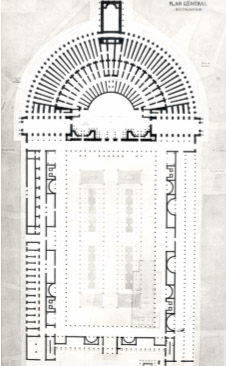

Baltard, restored plan of the Theater and peristyle of Pompey |

Baltard,

east-west section of the Theater of Pompey, looking

south

Baltard, north-south section of the Theater of

Pompey, looking east to the scaenae frons

|

||

| The south foundations of the Temple of Venus

Victrix photographed by Antonio Colini (c.1933)

|

During the three decades after Baltard, finds from the Theater of Pompey were, with one exception, largely unrecorded, but, in 1865, there was a second large-scale excavation. While Pietro Righetti, then owner of Palazzo Pio, was excavating the foundations for a new wing in the NE court, his laborers, working at a depth of 7.14 m, found, parallel to the north facade of the court, part of the south exterior wall of the Temple of Venus Victrix. Of peperino blocks, it consisted of the lower section of an arcade decorated with engaged half-columns.

Adjacent to the wall lay the remains of a street, a fine marble

pavement of porta santa and cipollino, and the gilt thumb from

a colossal bronze statue.

|

||

|

The Hercules Righetti as discovered in 1865 |

Directed by Architect Luigi Gabet, Righetti's workers made further

major discoveries. Excitedly increasing the size of their excavation,

Gabet and his workmen laid bare the rest of the statue, a colossal

Hercules (known today as the "Hercules Righetti"). It lay on its

back partially submerged under an ancient shelter of travertine

slabs at the SE corner of the foundations of the Temple of Venus

Victrix. The excavators raised it, and Righetti later sold it

to Pope Pius IX, who subsequently transferred it to the Sala Rotonda

in the Vatican Museums where it stands today.