By James Packer

Research Problems

After the excavation of the Hercules Righetti, despite

frequent chance finds of architectural elements and fragments of

sculpture, no serious archaeological investigations were carried out

on the site. All subsequent reconstructions and studies of the

Theater of Pompey, therefore, have necessarily been based, in the

most generalized fashion, on Baltard’s drawings, themselves

partially derived from the earlier study of Canina. But, while these

earlier investigations have given us much precious information on

the plan and architectural detailing of the theater, their random

and incomplete character leave many important questions unanswered.

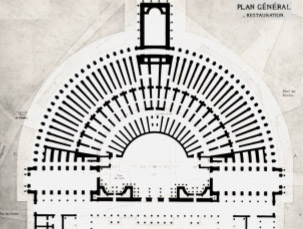

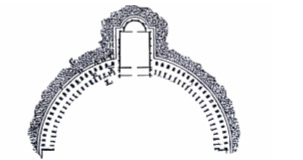

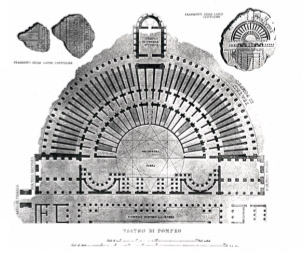

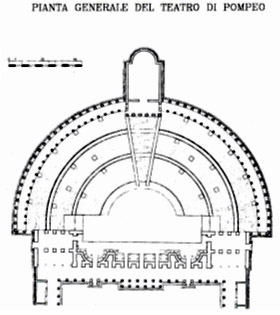

Was there an internal ambulacrum parallel to the

outer one and closer to the orchestra? Baltard shows two; Pellegrini

and Canina none, none.

|

|

|

| Baltard, Plan of the Theater of

Pompey |

|

|

|

| Pellegrini, Plan of the external ambulacrum

of the Theater of Pompey |

|

|

|

| Canina, Plan of the Theater of

Pompey |

How were the stairways positioned? Since neither Baltard’s

nor Pellegrini’s plans show them, we have no clear archaeological or

documentary evidence for the plan of the ground floor below the

seats of the cavea. And the plans of the interior of the cavea and

of the scaenae frons (the stage building) are equally

uncertain. Thus we do not know how closely later builders reproduced

Pompey’s Theater. Did they copy its plan and decor exactly?

Did they learn from its defects? How did they incorporate later

architectural innovations into Pompey’s August fabric? Without

precise documentation of the Theater’s accessible remains and

archaeological investigation of the surviving fabric, there were no

convincing answers to such questions. Indeed, as recently as 1997,

even a first-rate scholar like Filippo

Coarelli, in the section on the Theater of Pompey in his

comprehensive monograph on the ancient Campus Martius, reviewed only

the cadastral and literary evidence for the building.

Documentation: “The Pompey Project”

The Early Reconstructions

This was the state of scholarly knowledge on the Theater of Pompey

until 1996. Beginning in 1997, a team based at the University

of Warwick received a series of major grants successively from

the British Academy, the Leverhulme Trust, British The Arts and

Humanities Research Board and Warwick and Northwestern Universities

to enable a programme of extensive research and to undertake the

first ever scientific and comprehensive survey of the existing

state of the Theatre of Pompey. This work, directed by Prof. Richard

Beacham and co-directed by Prof. James Packer, was strongly endorsed

by the Archaeological Superintendent of Rome, Adriano La Regina.

The work in progress of the Pompey Project has produced many of

the materials selected for illustration here, and enabled the

excavations at the site which are currently being undertaken.

|

|

|

Letter of endorsement by the

Archaeological Superintendent of Rome |

Since its physical state had not been investigated since the

work of Baltard, the team began with study of the 19th

and early 20th century reconstructions by Canina, Baltard,

and Gismondi and with documentation.

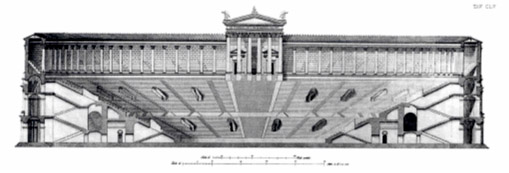

Canina, Section of Theater of Pompey looking west

Luigi Canina (1795-1856) undertook the first serious study of

the theater in 1835, pinpointing the four principal sources scholars

have subsequently used in their studies of the monument: (1) the

chance remarks of ancient literary sources; (2) Vitruvius’ essay on

the construction of the Roman theater (Book 3, chapter 5); (3)

the representation of the Theater on the Forma Urbis, and (4) study

of the surviving remains. Canina’s impressive results may be studied

both in his original drawings and in the three dimensional model

recently constructed by Martin Blazeby for the Pompey

project.

Luigi

Canina, Theater of Pompey, 3D model by Martin Blazeby, looking

SW

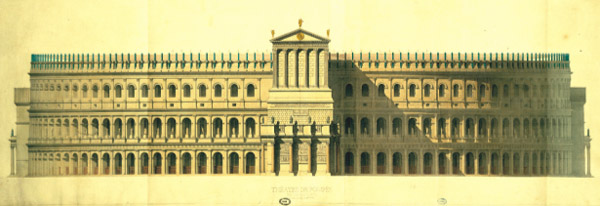

Two years after Canina’s study (1837), Victoire

Baltard undertook a second reconstruction of the Theater, basing his

work on Canina, but supplementing Canina’s work with several

knowledgeably located excavations that allowed him to make sensible

new suggestions on the character of the scaenae frons (the

stage) and the facade.

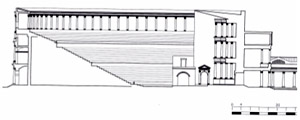

Without further original research, Italo Gismondi’s

reconstruction of the 1930s for the model of the city of Rome in

Rome’s Museum of Civilization combined the two earlier models and

added two buildings in the peristyle behind the scaenae frons.

(All the ancient sources locate gardens there, and Gismondi’s error

resulted from a misreading of the Forma Urbis).

Baltard,

Back of Theater of Pompey and the Temple of Venus

Victrix

Gismondi, Model of

the Theater of Pompey in the Museum of Roman

Civilization

The Documentation

Under the auspices of grants (to Prof. Beacham) from the British

Academy and Warwick University, Professors Beacham and Packer also

collaborated with Dario Silenzi and his team of architects in Rome

to produce the first modern plans, sections, and elevations of the

existing remains. This new documentation was essential. Although

Tata Giovanni had modern plans of Palazzo Pio –and gladly provided

copies, we had no means of checking their accuracy and that of

earlier site plans. Had Canina’s measurements been accurate? Those

of Baltard? Had Baltard and Canina drawn and located the

remains of the Theater accurately with respect modern block outlines

and street addresses? Earlier scholars–even so reliable a one as

Antonio M. Colini – usually identify the ancient remains by locating

them with respect to a modern business. Most of the businesses of

the 1930s and earlier have disappeared, however, and their exact

locations are not always certain. Accordingly, our plans (the

on-site measurements taken with a modern laser transit) show

the outlines of the blocks, street addresses, where possible, the

names of the establishments that currently occupy these premises,

and the ancient remains. For many of the latter, we also

provide sections and detailed elevations. Including aerial views,

pictures of all the modern building facades on the site, interior

views, and pictures of ancient rooms s and their

walls, our digital views supplement the measured

drawings.

Gismondi,

Plan of the Theater of Pompey

(Francesca Gagliardo) |

|

Gismondi, E-W

section of the Theater of Pompey looking N

(Francesca Gagliardo)

Tata

Giovanni, Partial plan of Palazzo Pio along Via di

Grotta Pinta and Piazza del Biscione |

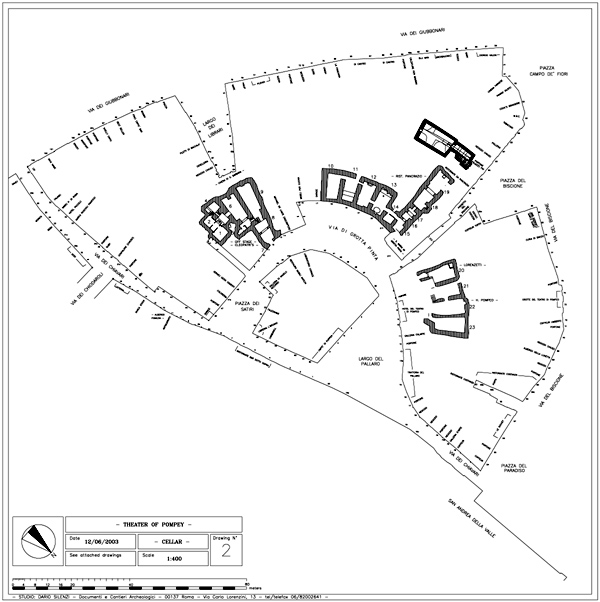

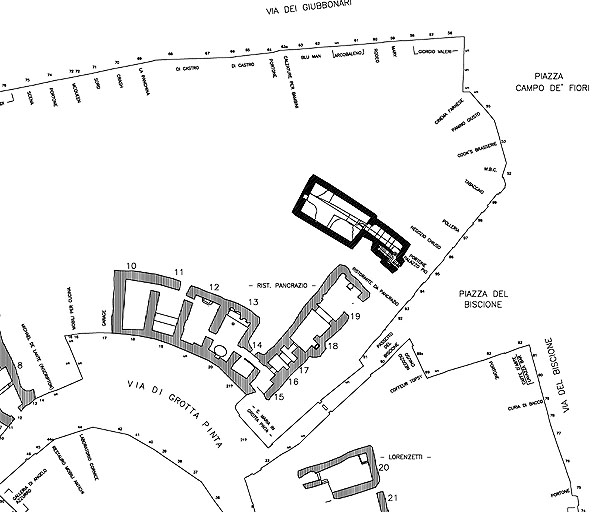

Site map showing

antiquities, addresses, and businesses on the Theater of Pompey Site

(Dario Silenzi)

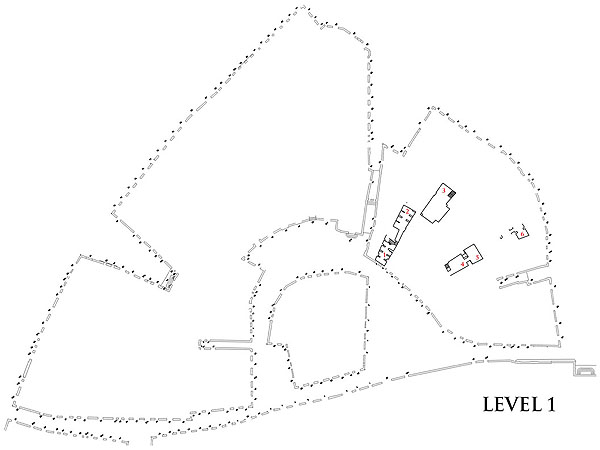

Theater of Pompey: Position of ancient

rooms, lowest level

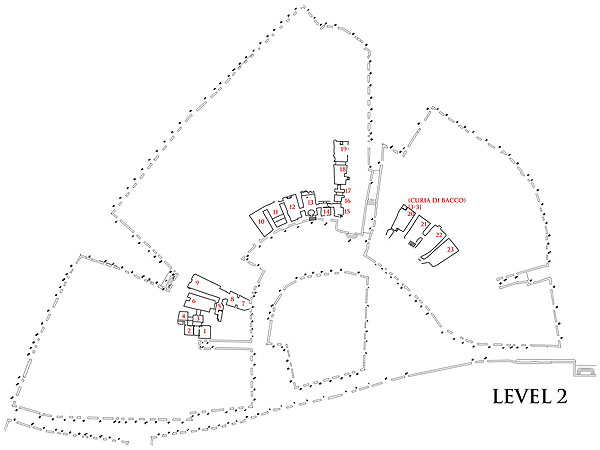

Theater of Pompey: Position of ancient rooms,

middle level

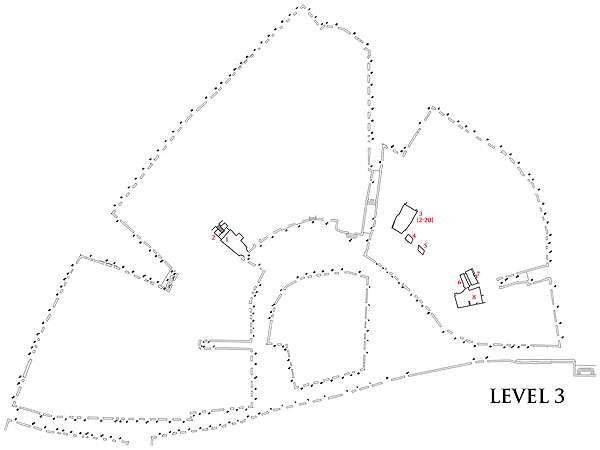

Theater of Pompey: Position of ancient rooms, upper

level

Ancient Rooms reached from “Ristorante

Pancrazio”

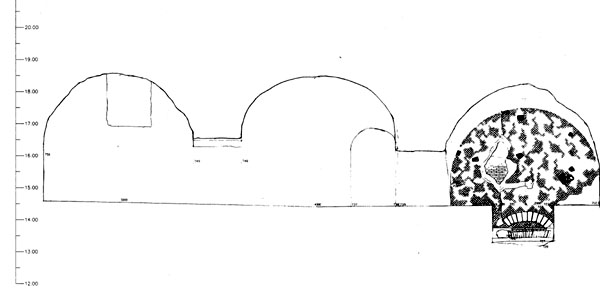

Section of some of the rooms (Nos. 10, 11, 12)

reached from “Ristorante Da Pancarazio,” looking west

Room 12 (digital view)

facing west